Laila Helmy, a history student at Cambridge University, examines how flexible and varied ideologies within Arab nationalist movements defy simple labelling, instead painting a nuanced picture of political thought.

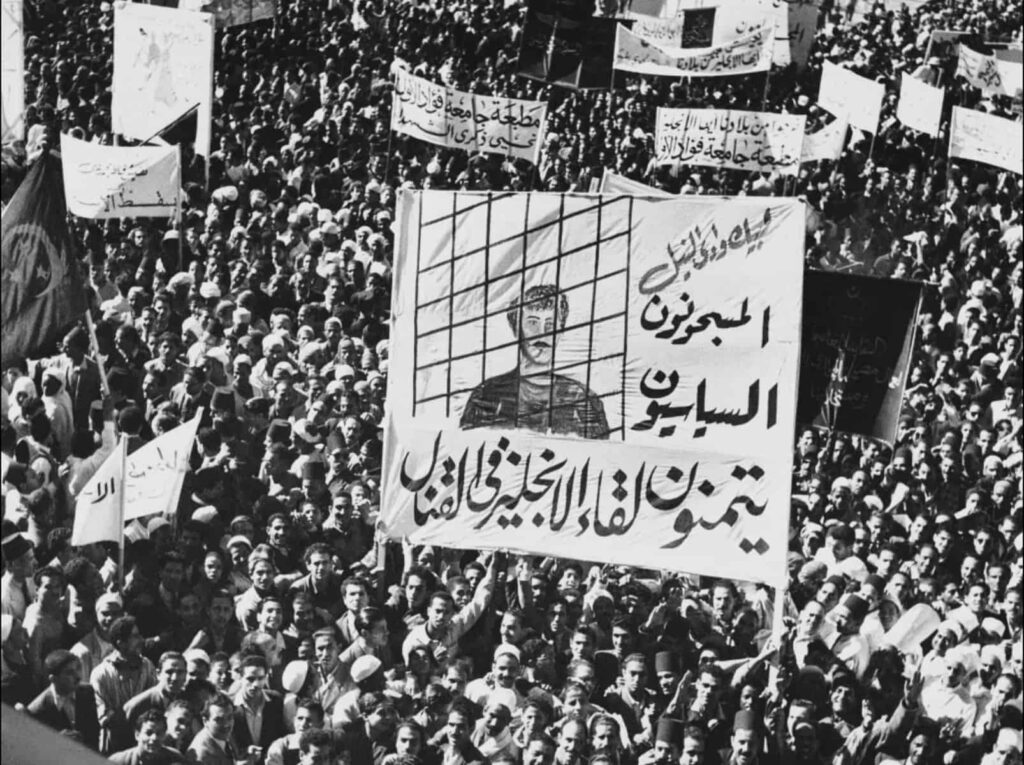

Authoritarianism and radicalism characterise contemporary views of the modern Arab world, particularly of the dominant ideologies, Arab nationalism and Islamism. Arab nationalism has been viewed through the prism of mid-20th-century nationalist movements, obscuring its period of liberal development in the first half of the century. It cannot be regarded as a distinct or coherent ideology during this period, as reflected by the variety of national visions expressed in the primary sources.[1] Liberal thought, expressed through the unifying force of anticolonialism, became central to political expression. Deviating from the rise and decline paradigm that ascribes an ‘end’ point to Arab nationalism is essential to express its heterogeneity and often contradictory nature, as it blended seemingly irreconcilable notions.[2] This period was one of ideological flux, not merely the precursor to a more authoritarian form of nationalism. Equally, liberal thought in the Arab world cannot be treated as a distinguishable ideology.[3] Liberal ideas, defined by Schumann as ‘modernity (as opposed to tradition); progress (as opposed to stagnation…); constitutional rule (as opposed to authoritarianism) … and democracy’ emerged as central tenets of various Arab nationalisms – often alongside seemingly irreconcilable illiberal ones.[4] Such contradictions expose the inherent limits of applying anachronistic labels to this period. Treating Islamic and liberal principles as mutually exclusive, or Western and liberal as synonyms, further obscures our understanding of the role of liberal thought. Assigning selective, westernising figures as liberal neglects the fluidity of nationalist thought and the presence of similar ideals amongst their opponents. Therefore, identifying this period as one of change and development is essential, as it highlights the constant presence of liberal thought within Arab nationalism, including within illiberal movements. The variety of attitudes towards Europe, discourse on the role of Islam and the emergence of increasingly radical and authoritarian forms of nationalism by the mid-century exemplify this heterogeneity.

The complex role of liberal thought within Arab nationalism is inseparable from the presence of conflicting attitudes towards the role of Europe and the West in shaping national identities and the future. While some viewed Europe as a model of national progress, others rejected Western civilisation as incompatible with the aims of national liberation, including Muhammad Abduh.[5] Taha Husayn’s conception of the ‘Egyptian mind’ in 1938 presents following the path of European civilisation as an organic development.[6] This rejection of anti-Western sentiments prevalent across the Arab world in the late 1930s, as anticolonialism adopted an increasingly radical face, is presented by Husayn as necessary for progress and to join the ‘civilized nations’ of Europe.[7] In advocating for Egypt to ‘do everything that they do’ to overcome its ‘feeble’ present, Husayn utilises the widely appealing liberal rhetoric of progress and the revival to reconcile national liberation with the emulation of European civilisation.[8] This construction of a historical bond between Egypt’s ‘Near East’ and the West, dating back to Pharaonic times, signifies the importance of maintaining an authentic Egyptian identity while modernising the nation.[9] Husayn’s rhetoric of progress, which emphasises the invaluable role of European influence in creating a superior and modern Egypt, reflects existing tensions, as liberal ideas were widely appealing yet perceived as inauthentic.[10] This perceived relationship between liberal thought and westernisation remains embedded within scholarship, exemplified by Hourani’s portrayal of al-Sayyid’s 1907 Hizb al-Umma as representatives of ‘liberal Islam’, and Kamil’s Hizb al-Watani as religious fanatics.[11] Omar’s rejection of labels applied by British officials to denote a liberal and an illiberal nationalism within Egypt emphasises the presence of liberal moods across party lines.[12] Both Kamil and al-Sayyid saw the modernisation of Egypt as necessary to achieving nationalist aims, exemplifying the hegemony of liberal notions of progress and subverting this dichotomy between Westernising ‘moderates’ and illiberal ‘fanatics’. As Omar illustrates, moderate and fanatic represented ‘taxonomies that had long been used’ by colonial officials, subverted by Egyptians to distinguish themselves, rather than to denote a clear political divide. [13]None of these actors would have labelled themselves as liberal; liberal ideas were expressed across the political spectrum.[14] Al-Khatib’s desire to construct a popular idea of the nation, writing in al-Asima in 1919, a time of increasing European political intervention, represents the widespread importance of liberal thought beyond Westernising narratives.[15] By pitting ‘individual interests’ against the collective national spirit, al-Khatib implicitly denounces national models based on ‘external’ and ‘limited’ foundations that contradict the ‘eternal… traditions’ of the nation.[16] While this rejection of external influences appears irreconcilable with Husayn’s project of European emulation, both view the progress and unity of the nation as necessary; it is their solutions that differ. Therefore, conflicting attitudes toward Europe and categorisations based on this have obscured the widespread role of liberal conceptions of progress across Arab nationalism.

The overemphasis of the role of Western intervention in shaping the liberal aims and worldviews of Arab nationalism has overshadowed its preexisting importance. The French presence in Greater Syria during the pivotal period following World War I has particularly skewed analyses of liberal Syrian thought. The King-Crane Commission report, alongside the resolution of the General Syrian Congress in 1919, exemplifies the fluid and often contradictory popular desires that emerged during this period.[17] The desire for ‘Absolute independence’, with 73% of petitions, emerged as central to anticolonial expressions of liberty.[18] However, Arab nationalist expressions were varied and flexible. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire had sparked increased European intervention in the region. Arab nationalists, therefore, aimed to appeal to Western rhetoric, embracing the ‘hierarchical logic of civilisational thought’ to gain concessions that aligned with preexisting national aims, as Arsan has argued.[19] The Syrian General Congress’s embracement of the ‘noble principles enunciated by President Wilson’ regarding self-determination represented a form of rhetoric, aiming to reject colonial intervention and assert a notion of self-determination that had existed before Wilson’s principles. This is highlighted by the Congress’s comparison of Syrians to ‘more advanced races’ to reject the application of the Mandate system to them; this does not constitute an imitation of Wilsonian principles, but rather illustrates the enduring legacy of liberal principles within Arab nationalism, expressed using Western rhetoric to gain concessions.[20]This entrenchment of liberal thought is further reflected in the Syrian constitution of 1930. As Zisser illustrates, it must be viewed as a ‘democratic and liberal statement’ of Syrian nationalism, rather than as a product of French intervention or the self-interest of leading Syrian notables, who acted as intermediaries between the French and society.[21] The writing of the Syrian constitution of 1930, like the discourse of 1919, reflected broad regional changes. Specifically, the press was reaching up to 300,000 people daily and established a network of ideological exchange across the Arab world.[22]For example, the liberal character of the Egyptian Revolution of 1919 reflected broad intellectual currents that defined Arab struggles for nationhood and unity within the period. Therefore, liberal thought within Arab nationalism cannot be attributed solely to Western intervention but rather reflected an existing tradition of Arab national thought and exchange.

The distinctions between Islamism and nationalism within scholarship have overshadowed the varied and often liberal role of Islam within Arab nationalism.[23] The relationship between Arab nationalism and Islam had not yet been defined during this period. Some intellectuals envisioned the emergence of an Islamic caliphate; however, Islam was also viewed as a shared Arab culture. Michel Aflaq’s writing in 1943 exemplifies this, as a Christian, Aflaq presents ‘true’ Islam as the ‘completion of Arabism’.[24] His use of Islam to construct a unified, ethnic nationalism highlights the role of Islam in establishing a secular nationalist identity. Furthermore, Aflaq’s view of Islam as reflective of the ‘fundamental character and virtues’ of all Arabs implies an inclusive, liberal conception of nationhood based on self-determination, regardless of religion.[25] Therefore, the connection between Islam and nationalism subverts modern categorisations of nationalism, Islamism and liberalism as distinct and irreconcilable ideologies. Secular reimaginations of Islam emerged during the Nahda, as secular Ottoman modernists sought to defend Islamic civilisation from European scrutiny, identifying it as compatible with a liberal, modernised state.[26] Al-Jawish took this further, claiming that Islam provided Protestantism with its ‘democratising tendencies… not the other way around’.[27] As a member of the Hizb al-watani, which has been deemed fanatical, al-Jawish’s liberal understanding of Islam subverts these distinctions entirely. Ultimately, categorisations obscure the nature of Arab nationalism as an undefined expression of desires reflective of broader political and social contexts. Al-Banna’s 1949 defence of an Islamic state expresses the heterogeneity of nationalist thought concerning Islam.[28] The Muslim Brotherhood, founded in 1928, symbolised the ability of Arab nationalism to unite contradictory liberal and illiberal ideas under the broader appeal of national liberation. Initially aiming for Egyptian independence from British intervention, al-Banna also emphasised the necessity of a ‘genuine’ Islamic revival and a moral revolution.[29] Advocating for the establishment of ‘Islamic law’ and the ‘punishment’ of dissenters, al-Banna’s national vision was one defined by an authoritarian leadership.[30] Nonetheless, the Muslim Brotherhood was an inherently modern conception, advocating for national unification based on religion, educational reform, and national liberation. Therefore, the variety within nationalist thought concerning Islam necessitates the rejection of anachronistic categorisations, dividing nationalism and Islam, or Islam and liberal thought.

Authoritarianism has been seen as the ‘end’ point of Arab nationalism, and a focus on this has led to the neglect of the continued importance of liberal thought within increasingly authoritarian nationalist movements in the 1930s.[31]Contradicting liberal notions of democracy and popular sovereignty, authoritarian tendencies have led to the wholesale condemnation of Arab nationalism as illiberal within scholarship. This is reductive, as it neglects the heterogeneity inherent within nationalist and liberal thought. As Schumann has highlighted, ‘liberalism’ was not a defined concept within the Arabic lexicon during this period.[32] Consequently, liberal ideas and institutions emerged, often in conjunction with authoritarian ones. Wien’s analysis of the Muthanna Club, founded in Iraq in 1935, exemplifies these complexities.[33]The Muthanna club’s values, like other organisations during this period, were ‘modelled on the symbols and practices’ of European fascism, as McDougall argues.[34] Al-Husri’s declaration that the nation sat ‘above everything, even above freedom’ in 1940 illustrates the prevalence of fascist ideals, including militancy, duty and authoritarian rule.[35] Yet, the Muthanna Club symbolises the fluidity of Arab nationalism, rather than its inexorable decline into authoritarianism. It reflected an emerging civil society centred around liberal notions of discourse, built on developments of the press and the public sphere. [36]Antun Sa’adah’s Syrian Social Nationalist Party, founded in 1932, further reflects this merger of fascist appearances with liberal aims of national liberation and unity.[37] Despite his inspiration by fascism, Sa’adah’s commitment to keeping Syria ‘free’ from Italian and German propaganda indicates the persistence of liberal and anticolonial views of national liberty.[38] Sa’ad’s militarised language of ‘duty’, exemplified in his description of the liberation of the nation ‘in well-organized ranks’, with men marching behind ‘giants of the army’, illustrates his combination of fascism and liberal thought, as militancy is seen as central, rather than as contradictory to liberation.[39]Therefore, this authoritarian turn of Arab nationalism does not confirm the paradigm of decline but rather reflects the fluidity of nationalist thought as simultaneously liberal and illiberal.

In conclusion, this period is characterised by the ideological development of Arab nationalism. It was broad and multifaceted, reflecting contradictory political expressions across the Arab world. However, national liberation and self-determination lay at the centre of nationalist thought, regardless of whether this was expressed through secular, constitutional or authoritarian movements. Therefore, Arab nationalism represented a liberal conception of Arab identity and the future of the nation. It simultaneously espoused seemingly irreconcilable beliefs, particularly in the 1930s and 1940s. Thus, the fluidity of Arab nationalism, and its interconnection with other political leanings showcases the necessity of rejecting the application contemporary categorisations of political thought on the Arab world of the early 20thcentury in future scholarship. The flexible nature of Arab nationalism, and its ability to reconcile liberal and illiberal visions reflects the transformation, and instability of the region during this time. Thus, understanding the contradictory nature of Arab nationalism is essential to recognising the continued importance of liberal thought on various forms of nationalist thought throughout the period.

[1] Christoph Schumann, ed., Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East: Ideology and Practice (2009) p. 224

[2] James McDougall, ‘The Emergence of Nationalism’, in Amal Ghazal and Jens Hanssen, eds. Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle Eastern and North African History (2020) p.128

[3] Schumann, Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East p.223

[4] Christoph Schumann, ed. Liberal thought in the Eastern Mediterranean: late 19th century until the 1960s (2008) p.3

[5] See Ernest Dawn, From Ottomanism to Arabism: Essays on the Origins of Arab Nationalism (1973) p388, Muhammad Abduh rejected Western civilisation on the basis that Islam was perfect.

[6] Taha Husayn, The Future of Culture in Egypt, trans. Sidney Glazer, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East (2004) p.168

[7] Husayn, The Future of Culture in Egypt, trans. Glazer, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.167

[8] Husayn, The Future of Culture in Egypt, trans. Glazer, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, pp.167 and 169

[9] Husayn, The Future of Culture in Egypt, trans. Glazer, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.170

[10] Schumann, Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East, p.221

[11] Hussein Omar, ‘Arabic Thought in the Liberal Cage’, in Faisal Devji and Zaheer Kazmi, eds., Islam After Liberalism (2018) p.19. Here, Omar discusses Albert Hourani, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798-1939 (1962)

[12] Omar, ‘Arabic Thought in the Liberal Cage’, in Devji and Kazmi, eds., Islam After Liberalism, p.21

[13] Omar, ‘Arabic Thought in the Liberal Cage’, in Devji and Kazmi, eds., Islam After Liberalism, p.24

[14] Schumann, Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East, p.224

[15] Muhib al-Din al-Khatib, “Public Opinion”, al-Asima, 23 October 1919, vol 1, no.69, trans. Akram Khater, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p. 209

[16] al-Khatib, “Public Opinion”, al-Asima, trans. Khater, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p. 211

[17] The Resolution of the General Syrian Congress, from the King-Crane Commission Report, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p. 201 and King-Crane Report on The Near East, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p. 203

[18] King-Crane Report, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p. 204

[19] Andrew Arsan, ‘The Patriarch, the Amir and the Patriots: Civilisation and Self-Determination at the Paris Peace Conference’, in T.G. Fraser, ed., The First World War and its Aftermath: The Shaping of the Middle East (2015), p.139

[20] Resolution of the General Syrian Congress, , in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.201

[21] Eyal Zisser, ‘Writing a constitution: Constitutional Debates in Syria in the Mandate Period’, in Christoph Schumann, ed. Liberal thought in the Eastern Mediterranean: late 19th century until the 1960s (2008) pp. 195-215. See Philip S. Khoury, ‘Continuity and Change in Syrian Political Life: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’, AHR 96, 5 (1991) on the role of urban notables as intermediaries between the French and their local society.

[22] [22] Zisser, ‘Writing a constitution: Debates in Mandate Syria’, in Schumann, ed. Liberal thought in the Eastern Mediterranean, pp.210-11

[23] McDougall, ‘The Emergence of Nationalism’, in Ghazal and Hanssen, eds. Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle Eastern and North African History ), p.138

[24] Michel ‘Aflaq, Choice of Texts from the Ba’ath Party’s Founder’s Thought, trans., Akram Khater, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, pp.170 and 173

[25] Aflaq, Choice of Texts from the Ba’ath Party’s Founder’s Thought, trans., Akram Khater, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.173

[26] Ernest Dawn, From Ottomanism to Arabism: Essays on the Origins of Arab Nationalism (1973), p.386

[27] Omar, ‘Arabic Thought in the Liberal Cage’, in Devji and Kazmi, eds., Islam After Liberalism, p.31

[28] Five Tracts of Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949)., trans, Charles Wendell (1978), in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.175

[29] Five Tracts of Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949)., trans, Wendell, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East,p.177

[30] Five Tracts of Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949)., trans, Charles Wendell (1978), in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.179

[31] McDougall, ‘The Emergence of Nationalism’, in Ghazal and Hanssen, eds. Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle Eastern and North African History ), p.138

[32] Schumann, Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East, p.123

[33] Peter Wien., ‘Who is “liberal” in 1930s Iraq?’., in Christoph Schumann, ed., Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East: Ideology and Practice (2009) pp. 52-72

[34] McDougall, ‘The Emergence of Nationalism’, in Ghazal and Hanssen, eds. Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle Eastern and North African History ) p. 137

[35] Wien, ‘Who is “liberal” in 1930s Iraq?’., in Christoph Schumann, ed., Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East, p. 62

[36] Wien, ‘Who is “liberal” in 1930s Iraq?’., in Christoph Schumann, ed., Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East, p. 57

[37] Antun Sa’adah, Speech given in 1935 in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.164

[38] Antun Sa’adah, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.165

[39] Antun Sa’adah, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.166

Bibliography:

Primary sources:

- Aflaq, Michel Choice of Texts from the Ba’ath Party’s Founder’s Thought, trans., Akram Khater, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, pp.170-175

- Al-Banna, Five Tracts of Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949)., trans, Charles Wendell (1978), in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East pp175-181

- al-Din al-Khatib, Muhib “Public Opinion”, al-Asima, 23 October 1919, vol 1, no.69, trans. Akram Khater, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East pp.209-211

- Antun Sa’adah, Speech given in 1935 in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, p.164

- Husayn, Tahya , The Future of Culture in Egypt, trans. Sidney Glazer, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East (2004) pp.166-70

- King-Crane Report, in Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, pp. 203-209

- The Resolution of the General Syrian Congress, from the King-Crane Commission Report, in Akram Khater, ed., Sources in the History of the Modern Middle East, pp.201-202

Secondary reading:

- Arsan, Andrew ‘The Patriarch, the Amir and the Patriots: Civilisation and Self-Determination at the Paris Peace Conference’, in T.G. Fraser, ed., The First World War and its Aftermath: The Shaping of the Middle East (2015), pp. 127-45

- Dawn, Ernest , From Ottomanism to Arabism: Essays on the Origins of Arab Nationalism (1973)

- Hourani, Albert, Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798-1939 (1962)

- Khoury, Phillip, ‘Continuity and Change in Syrian Political Life: The Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’, AHR96, 5 (1991)

- McDougall, James ‘The Emergence of Nationalism’, in Amal Ghazal and Jens Hanssen, eds. Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle Eastern and North African History (2020)

- Omar, Hussein , ‘Arabic Thought in the Liberal Cage’, in Faisal Devji and Zaheer Kazmi, eds., Islam After Liberalism (2018) pp. 17-45

- Schumann, Christoph ed. Liberal thought in the Eastern Mediterranean: late 19th century until the 1960s (2008)

- Schumann, Christoph ed., Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East: Ideology and Practice (2009)

- Wien, Peter ‘Who is “liberal” in 1930s Iraq?’., in Christoph Schumann, ed., Nationalism and Liberal Thought in the Arab East: Ideology and Practice (2009) pp. 52-72

- Zisser, Eyal, ‘Writing a constitution: Constitutional Debates in Syria in the Mandate Period’, in Christoph Schumann, ed. Liberal thought in the Eastern Mediterranean: late 19th century until the 1960s (2008) pp.195-215