Freddy Purcell–

Over November we were lucky enough to have three guests speak on a variety of topics and in a variety of styles. It was greatly enjoyable for me to find out more about the research the lecturers undertake while they’re not dealing with us, so I hope you enjoyed the talks as well. Since it has now been a term of Phil on Taps and me writing summaries for them, if anyone has any feedback about the events or the write-ups then please do leave a comment down below. We always want to make Philosophy Society events as good as possible, and I want to make Notion’s articles as engaging as possible. This is likely to be the last article we publish this year, so thank you for reading Notion and happy holidays!

Talks included in this summary: Adrian Currie on dinosaur art, Tom Roberts on embodied cognition in AI and Sam Wilkinson on organic personality change.

Phil on Tap 07/11/24: Adrian Currie- Why did dinosaurs look like that?

Adrian’s talk was the most unique and entertaining Phil on Tap we’ve held in all my one and a half years in Philosophy Society. Adrian structured the talk around photos to illustrate his points about the development of paleoart, but he also brought along the Cellist Beth Porter, who he has been working with recently, to react to each photo (without having seen it before) by improvising a short tune. While I am afraid that I cannot include the Cello playing in this summary, I hope this conveys just how fun the talk was to attend.

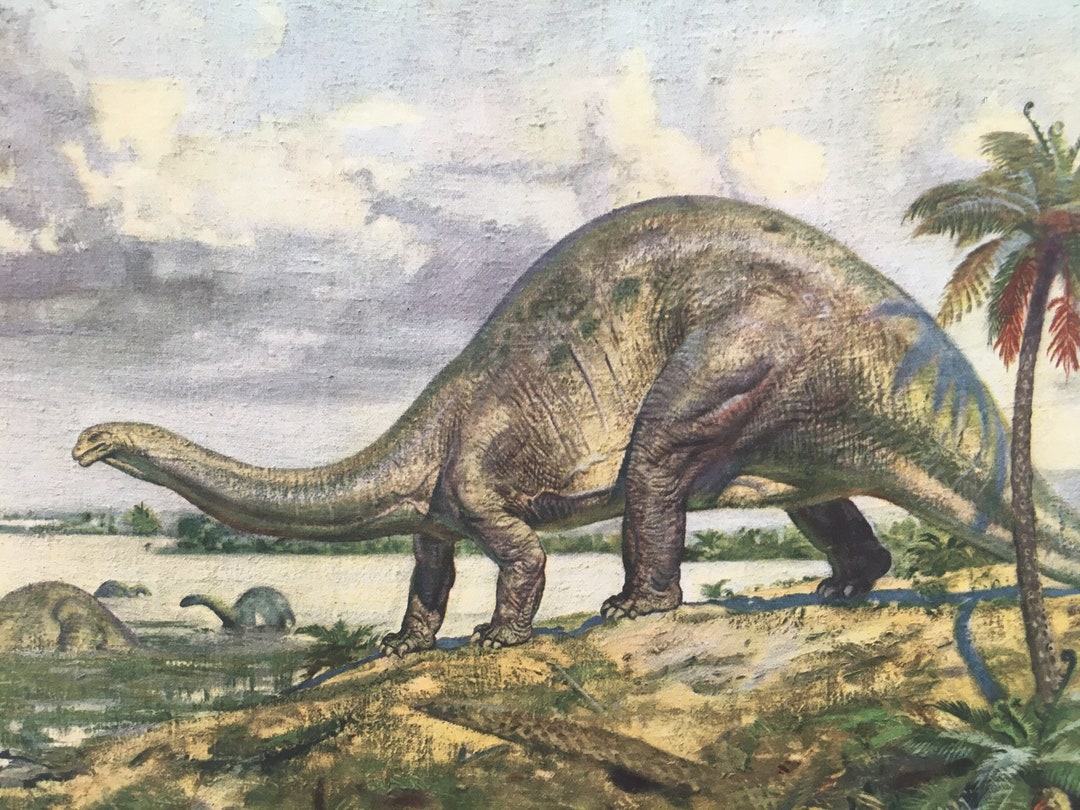

The first photo Adrian showed us was an illustration from the 1960’s of a Brontosaurus. Everyone generally agreed that it just looked wrong, with someone in the audience pointing out that its neck to back ratio makes it look particularly odd. It is probably this ratio that prompted quite a sad funky tune from Beth.

- Brontosaurus from 1960s

We then moved on to a drawing from 1978 showing two dinosaurs fighting, that the audience agreed was a far more exciting depiction as it is more dynamic with a classic ‘Godzilla’ feel to the dinosaurs. Adrian attributes this difference in feeling to a change in paleoart in the late 60s where dinosaurs started to be drawn in a shrink-wrapping style that emphasises the muscles of the dinosaurs. Adrian argues that this dynamism portrays dinosaurs more like living beings but questions the extent to which this is informed by science.

- Dinosaur fight from 1978

For the third drawing, Adrian showed us a cartoon character from an upcoming book, Professor Ichthy. The difference between the a cartoon depiction and a shrink-wrapped drawing felt vast, but the form of Professor Ichthy is fully informed by modern thinking on dinosaurs’ appearances. The shrink-wrapping method therefore seems to idealise the form of dinosaurs, much like Roman or Greek art did to the human form. This idealisation has a function, as Adrian described how shrink-wrapping exists to try and portray dinosaurs in a scientifically accurate way by removing the elements that we don’t know much about. For example, we know a lot more about the muscles and bones of dinosaurs, so these elements are emphasised in shrink-wrapped depictions. However, we are not so sure about the fats and tissues of dinosaurs, so they are omitted from drawings. This underlines an issue in Adrian’s mind because we know that shrink-wrapped drawings don’t represent what dinosaurs actually looked like, but this is still what we all imagine when we think of dinosaurs.

To extend this point, Adrian then showed us both a portrait and a photograph of his cat Misty Shadowfang. This prompted Beth to produce meowing noises from the Cello, which was not something I ever thought I’d hear. Neither depiction of Misty was hyperbolic, and instead accurately represented Misty’s form as it would be experienced in real life. To therefore make something realistic, Adrian argues that we must include colour and the sorts of properties that we know less about in dinosaurs.

The sixth drawing that Adrian showed us was one of these possible depictions of dinosaurs that fills in what we don’t know while sticking to scientific accuracy. It is a depiction of a Carnataurus from the book All Yesterdays by Conway, Koseman and Naish that aims to fight back against shrink-wrapping styles with alternative illustrations of prehistoric life.

- Alternative Carnataurus

This same book also shows how weird it would be to draw living creatures in a shrink-wrapping style, with Adrian showing us the horrors of a shrink-wrapped cat. If you haven’t experienced these drawings before I would really recommend looking them up, shrink-wrapped swan is a favourite of mine…

- Shrink-wrapped cat

Adrian therefore argues that shrink wrapping fails as a way of illustrating dinosaurs because it leads to bizarre misconceptions about the appearance of creatures. Adrian pointed out that it is difficult to know how to depict dinosaurs as we want to aim for realistic and exciting art, while also avoiding the sort misconceptions that methods like shrink-wrapping bring about. The solution he therefore suggests is to form a diversity of representations, that would include cartoons or the alternative drawings shown above, that realistically fill in the details of what we don’t know while sticking to scientific thinking.

The talk then ended with a beautiful performance of Beth’s own song, ‘Deep Time’.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Phil on Tap 14/11/24: Tom Roberts- Embodied Cognition and Artificial Minds.

This talk was born from research that Tom is currently undertaking on whether Artificial Intelligences like Chat GPT are minds from the perspective of embodied cognition. This position argues that the mind is fundamentally embodied, raising questions about whether artificial intelligence could ever have a mind.

To evidence this point, Tom detailed several different mental states that have deep links to embodiment. For example, the interoceptive states of being drunk, or relaxed or physically uncomfortable are deeply linked to how we feel in our bodies. Tom pointed out that you need teeth to have a toothache, so Chat GPT is unlikely to be able to experience a tooth ache. Affective states like being angry also come with physical elements, like being angry can make someone shake, or sweat, or grow red in the face.

Spatial content and visual phenomena are also determined by the body. Tom used Peacock’s example of how experiencing Buckingham Palace from side-on is different to experiencing it head on. Many other experiences also rely on the body such as how we use touch to explore the material world, or how our visual memory relies on sight, or embodied knowledge like the ability to play a musical instrument. Taking all this into account Tom concluded that AI is limited in its capabilities, being like the mind that Descartes imagined would exist without a body. This sort of mind may be able to compute things like mathematics but would have such a narrow existence as to make it a very strange sort of mind.

Taking this into account, part of Tom’s research is to then assess how we approach AI systems with these limitations in mind. He wants to argue for a sort of fictionalist account where we treat AI systems like actors on a stage that perform a role, like telling us about their existence, but we know they are telling the truth as such. An audience member pointed out that some systems are very honest about their limitations, stating that they don’t know about some human affairs. There may be a way in which our communication with the AI is fictitious itself, for example our language usage, but Tom admitted this is a part of his project that he needs to work on.

There were several very strong questions that really tested Tom’s argument and pointed to parts that he wants to work further on. Some people questioned the possibility of AI having a different sort of embodied existence, be it through some sort of virtual body or through a complex robotic system. Tom replied that even if you could enrich the experience of an AI, it would still fall more into the category of a weird sort of Cartesian disembodied mind. Other questions explored whether we really need a body for certain sensations, for example physical sensations in dreams or phantom pain in limbs. This drew out Tom’s supposition that we cannot experience physical phenomena like visions without having had some experience of these phenomena. He admitted that this is a debatable position, but there is some evidence to suggest that without continuous input, something like our visual imaginations become increasingly distorted.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Phil on Tap 28/11/24: Sam Wilkinson- Organic Personality Change.

Sam’s talk comes from many years of working the Brain Injury Charity, Headway, so his passion for the topic was apparent and his talk was even more engaging for it. Sam begun by describing the process of diagnosis of organic personality change and what it actually is. After a physically traumatic incident, when someone’s physical condition is stable, the next step is standardised testing on that person’s mental capabilities. The scores of these tests are then sent back to loved ones to warn them of issues in speech or memory. The process for organic personality change is quite different because it relies on the testimony where loved ones say that someone has changed since the traumatic incident or the person that experienced this incident feels that they themselves have changed. This process is subjective and can often lead to discrepancies between the accounts of the person that suffers the trauma and the people around them. However, these testimonies have the weight to provide people with diagnoses for organic personality disorder where there is considered to be severe personality change. Organic personality is therefore a construct that is used internationally, but without any clear guidance of what to look for in diagnosis beyond asking people how they feel after a severely traumatic incident.

In light of what Sam sees as a messy and problematic process, he therefore looked to better define organic personality change. He begun by separating non-organic changes from organic changes, the former being where we respond to life experiences naturally and often rationally. This leads to ambiguous territory because it would be very rational for someone to feel angry after having a traumatic incident that damaged their brains, showing that non-organic personality change is possible after these incidents. Sam also differentiated organic personality change from illnesses that cause disinhibition such as dementia, where people often thought to have their personality ‘in there somewhere’, as opposed to having their personality undergo subtle but profound changes.

Sam then explored some more of the issues arising from organic personality change. One of those issues is self-alienation where someone remembers and likes the person they were before the incident but hates who they are now and finds their actions reprehensible. This then causes people to distance themselves from their personalities and is extremely distressing. Another issue surrounds the decisional capacity of someone after a brain injury as they may be functional and autonomous, but it is unclear whether they ought to be legally able to make decisions on behalf of their formal self. For example, in the classic case of someone changing their will to disinherit their family. Sam concludes that there are also therefore legal holes surrounding personality change.

Owing to all the issues around diagnosis for this serious problem, some scholars argue that we should get rid of the category of personality change and break it up into its parts, for example, disinhibition or anger management issues. Once personality change is split up into symptoms it isn’t really personality change anymore, but a series of issues that we understand and can deal with better. Sam objects to this initially on the basis that it seems belittling to say to loved ones of someone that has suffered from a brain injury that their personality wasn’t real anyway.

Sam instead argues that we should reassess how we view personality. He argues that as social animals we attributed personality traits to others to build reputations for community members. Reputation only functions if we have the idea that someone labelled as ‘bad’ remains ‘bad’ over time. Sam therefore argues that personality is a value laden thing, which fits with how personality change is often reported when someone feels like a trait they valued in someone has disappeared. This is particularly the case in moral traits, where someone might be loved by a spouse for their kindness, but a brain injury makes them callous. Sam therefore argues that if we were to break down personality change into its parts, then this misses the wider picture of what personality is. This understanding is needed to understand how people experience the personalities of themselves and others.

The main lessons that Sam concluded with were that we shouldn’t view personality as a descriptive thing, but as value laden and perspectival. This then means that personality is a cultural and social entity, as what a person values is influenced by their context. Using this view of personality, we should then rethink the temporality of personality change. Clinically speaking, there is a clear before and after when someone undergoes a traumatic event but little nuance to this. This means that if someone is diagnosed with organic personality disorder and considered problematic for something like anger management issues, then this can be put on their permanent medical record. For example, Sam has met several people that struggled with anger management that have mellowed over time, but the medical institution has labelled them as having issues causing this to get flagged by systems through their lives, potentially affecting how they’re treated. Sam also describes how loved ones around a person with organic personality change often think that it will be permanent and therefore abandon that person before they have a chance to change for the better. Sam argues therefore that rethinking the temporality of personality change is key. One possible improvement would be to introduce a minimum amount of time before organic personality change can be diagnosed, respecting both the possibility for changes away from problematic behaviour and the impact that a highly traumatic incident might have on someone’s personality.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

If you have got this far, thank you for reading! And thank you to our amazing speakers for giving these deeply engaging talks!