Isaac McManus explores the hermeneutical injustice perpetrated through literacy laws against enslaved people, pointing out some flaws in Fricker’s original description of injustice and detailing some of its nuance.

(This essay was adapted from Knowledge and Reality 2 coursework)

Within this article I shall advance an analysis of Miranda Fricker’s conception of systematic hermeneutical injustice via a case study of literacy laws in the Antebellum South, which restricted the ability of both enslaved and freed black people from being able to contribute to the shared pool of human knowledge. To define terms, systematic hermeneutical injustice occurs according to Fricker as: “the injustice of having some significant area of one’s social experience obscured from collective understanding owing to a structural prejudice in the collective hermeneutical resource” (Fricker, 2006, p.100). This occurs due to hermeneutical marginalisation, whereby a specific social group is left underserved by unequal hermeneutical participation (ibid. 98-99). This alienation from one’s ability to communicate has severe consequences on an individual’s ability to both comprehend, and effectively protest, their own mistreatment (ibid. pp. 103-104).

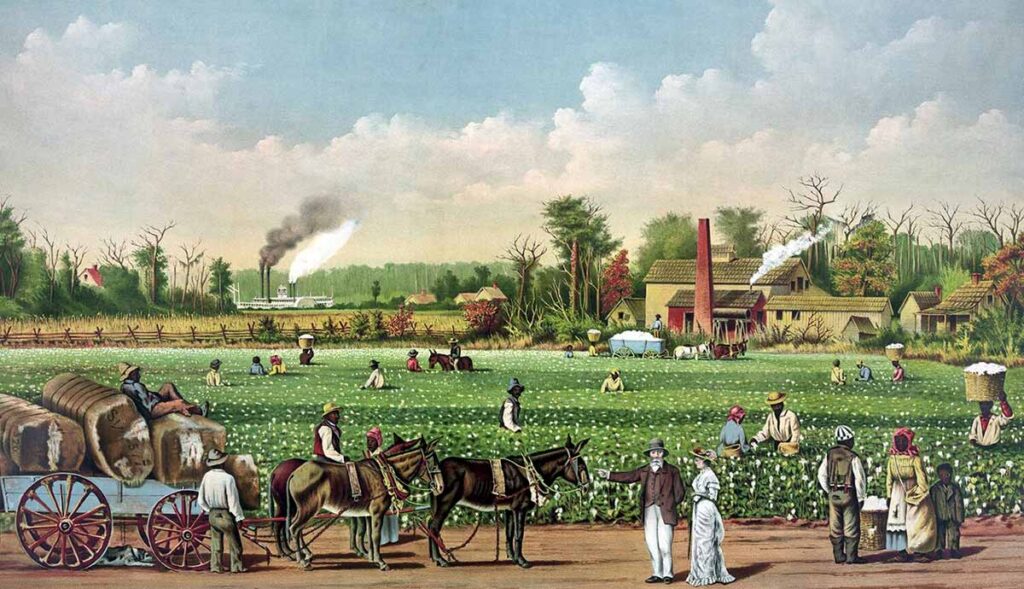

It is first wise to characterise what literacy laws were. Literacy laws were a series of inter-weaving ordinances, passed by (pre-dominantly though not exclusively) slave state legislations prior to the American Civil War, criminalising and preventing enslaved and freed black people from being taught to read or write (Span, 2005). With the earliest recorded American literacy law being made in 1740 Colonial South Carolina, prior to American independence (Rasmussen, 2010), these laws would proliferate across the United States throughout the 18th and 19th Centuries (Span, 2005, pp. 27-35). Often these laws would include punishments for both enslaved people learning to read and write, as well as those who would seek to teach them (ibid. pp 27-28). The net effect of this is that enslaved people[1] were by and large excluded from literacy.[2]

I shall seek to explain the multiple overlapping manners in which these laws characterise an epistemic and hermeneutical injustice, starting with the general, before moving on to the specific. Firstly, this obviously characterises the kind of ‘distributive injustice in epistemic goods’ which Fricker characterises explicitly in terms of lack of access to education (Fricker, 2007, p.1). Fricker goes on to state that this form of injustice is not within the scope of her book, as the injustice is seemingly only epistemic in so far as it relates to an epistemic good. I shall contest this position by demonstrating how this seemingly ‘mundane’ injustice in fact gives rise to several injustices decidedly epistemic in-character. Firstly, this distributive injustice gives rise to an epistemic injustice in the broad sense of the term defined by Fricker that “any epistemic injustice wrongs someone in their capacity as a subject of knowledge”, which is to say, their ability to contribute to, or take value from, the sum pool of human knowledge (ibid. p. 5). Beyond this, the distributive injustice goes on to form the backdrop for a structural prejudice which gives rise to a deficit in the collective hermeneutical resource, a clear case of hermeneutical marginalisation, and the creation of conditions prime for the eruption of hermeneutical injustice.

As presented by Fricker in the sexual harassment example (Fricker 2006, pp. 96-97), the issues raised by a hermeneutical injustice are often addressed when a group of victims of a hermeneutical injustice collaborate to identify and name the lacuna in concepts needed to describe their experience. Literacy laws specifically prevented this in three ways, and in doing so caused hermeneutical marginalisation by causing unequal hermeneutical participation, sowing the seeds for an eruption of hermeneutical injustice.

Firstly, they greatly limited the scope of conversation for enslaved people to solely others enslaved in the same locale as them, reducing opportunities for the communal sharing of ideas and experiences required to create corrections for the lacuna. This is because the lack of a capability to read and write, as well as restrictions placed on enslaved people by enslavers limiting their ability to see others, meant that only the spoken word, with a limited number of people, was available as a means of communication for enslaved people.

Secondly, literacy laws would prevent the dissemination of correction for a lacuna from a localised group of enslaved people to the wider population. In the case presented by Fricker of sexual harassment, the Women’s Lib Movement would spread awareness of the term sexual harassment, filling the lacuna, and correcting a major epistemic injustice. Literacy laws would prevent any correction of a lacuna made by an enslaved group outside of their social circle by limiting access to the print media and written word which constituted the main form of social communication at the time.

Finally, even if terms were created to fill a lacuna in the language of the treatment of enslaved people by an external group[3], the underlying structural marginalisation caused by an inability to read would prevent enslaved peoples from gaining access to these terms. This would create a localised lacuna, even if amongst literate populations no lacuna exists. Indeed, this is somewhat similar to the issue raised by Carel & Györffy (Carel and Györffy, 2014, pp. 1256-1257), with regards to young patients in a medical setting, where a positional lack of access to shared hermeneutical resources creates a localised lacuna, despite terminology existing to bridge that lacuna in wider society.

Stemming from this, we see that this state of affairs therefore meets the conditions of being embedded within social structures and not being a case of “circumstantial epistemic bad luck” (Fricker, 2006, p. 98). It arises from a powerlessness and serves an implicit coercive social purpose of limiting the scope of available conversation. To adopt Fricker’s terminology, the enslaved are “hermeneutically marginalised”, and “… it was no accident that their experience was falling down the hermeneutical cracks,” (Ibid. p.99). Indeed, Fricker’s argument that “one hermeneutical rebellion inspires another” by granting epistemic courage in the face of oppression provides a potential explanation for why these literacy laws were created in the first place (Fricker 2007, pp. 167-168). Indeed, the argument that literacy laws were primarily passed as a manner for preventing the communication and unity amongst enslaved people is strongly supported by the historical record, with South Carolina twice framing incredibly draconian literacy laws as a response to, and prevention of, uprisings (Rasmussen, 2010, pp. 201-202) (Span, 2005, p.27).

[1] And in many cases, also freed black people

[2] Barring notable exceptions such as presented by Cornelius (Cornelius 1983)

[3] For example, by abolitionists.

Bibliography:

- Carel, H. and Györffy, G. (2014) ‘Seen but not heard: children and epistemic injustice’, The Lancet, 384(9950), pp. 1256–1257. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61759-1.

- Cornelius, J. (1983) ‘“We Slipped and Learned to Read:” Slave Accounts of the Literacy Process, 1830-1865’, Phylon (1960-), 44(3), pp. 171–186. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/274930.

- Dular, N. (2023) ‘One Too Many: Hermeneutical Excess as Hermeneutical Injustice’, Hypatia, 38(2), pp. 423–438. Available at:10.1017/hyp.2023.20.

- Fricker, M. (2006) ‘Powerlessness and Social Interpretation’, Episteme, 3(1–2), pp. 96–108. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/episteme/article/powerlessness-and-social-interpretation/FA8C52ECB5514A9324DC6F5713FF6292.

- Fricker, M. and Oxford University Press. (2007) Epistemic injustice : power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford ; Oxford University Press.

- Luzzi, F. (2024) ‘Deception-Based Hermeneutical Injustice’, Episteme, 21(1), pp. 147–165. doi:10.1017/epi.2021.7.

- Morton, T. (2013) Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Vancouver ; U of Minnesota Press.

- Rasmussen, B.B. (2010) ‘“Attended with Great Inconveniences”: Slave Literacy and the 1740 South Carolina Negro Act’, PMLA, 125(1), pp. 201–203. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25614450.

- Span, C.M. (2005) ‘Learning in Spite of Opposition: African Americans and their History of Educational Exclusion in Antebellum America’, Counterpoints, 131, pp. 26–53. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/42977282.