Freddy Purcell-

Welcome back to a new term (and calendar year) of Phil on Tap! Thank you to all those that showed up and to Kirsten for her brilliant talk.

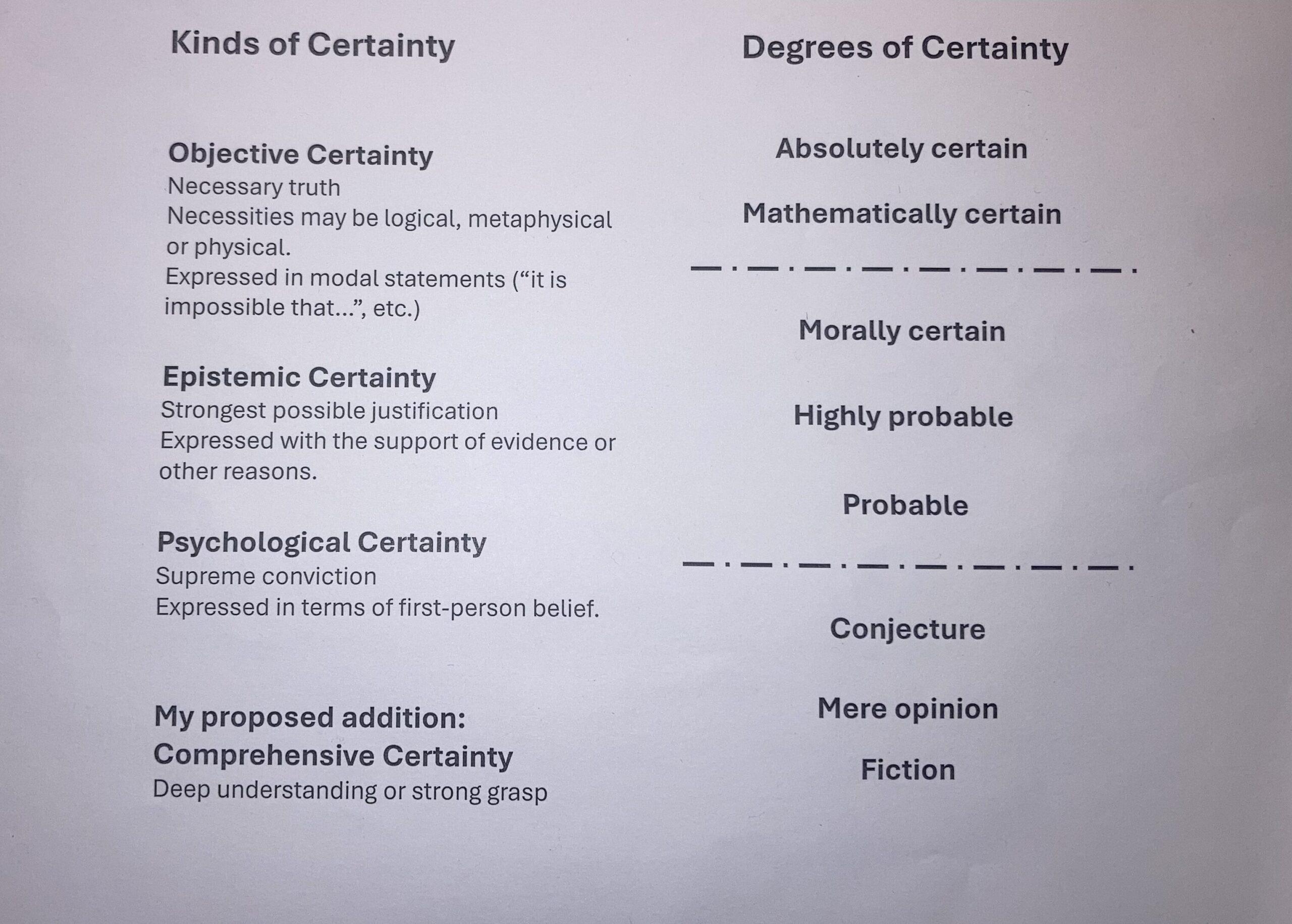

The talk centred around Kirsten’s current research into certainty, which she defined loosely as an ideal absence of doubt that is greater that belief or opinion. She pointed to further debate about how certainty relates to knowledge, for example, whether it is a subsection of or the same thing as knowledge. However, Kirsten put this debate aside and instead focussed on how certainty differs in both kind and degree, providing us with a list compiled from her extensive reading on the subject.

In terms of degrees, Absolute Certainty is the sort of certainty that would be held by God, and maybe certain angels, as it requires omniscience. Mathematical certainty then relates to self-evident truths, such as those found within mathematics. These two certainties fall into the category of compelled assent, a term derived from Descartes, and are the only forms of true certainty. Moral certainty is another term taken from Descartes and is unrelated to ethics. Instead, it relates to the sort of truth that is sufficient to guide correct action but is revisable. For example, scientific models may yield highly accurate predictions that are functional to act upon but may be open to revision in light of future discoveries. The second section of degrees of certainty therefore relates to levels of probability of truth, while the final section has an even more distant relation to knowledge and truth.

On Kirsten’s list of kinds of certainty, objective certainty represents necessary truth, such as the classic ‘all Batchelors are unmarried men’. The relationship to necessity means that these sorts of statements are often put in modal terms of possibility or impossibility. Epistemic certainty then represents the strongest possible support for a belief, so it could be that all material evidence and logical evidence points us to this sort of conclusion. Finally, psychological certainty is more of a statement of personal conviction, that often relates to the above forms of certainty, but does not necessarily. For example, Kirsten mentioned a classic example in the literature of a mother holding the psychological certainty that her child is not a murderer, despite overwhelming evidence that they are.

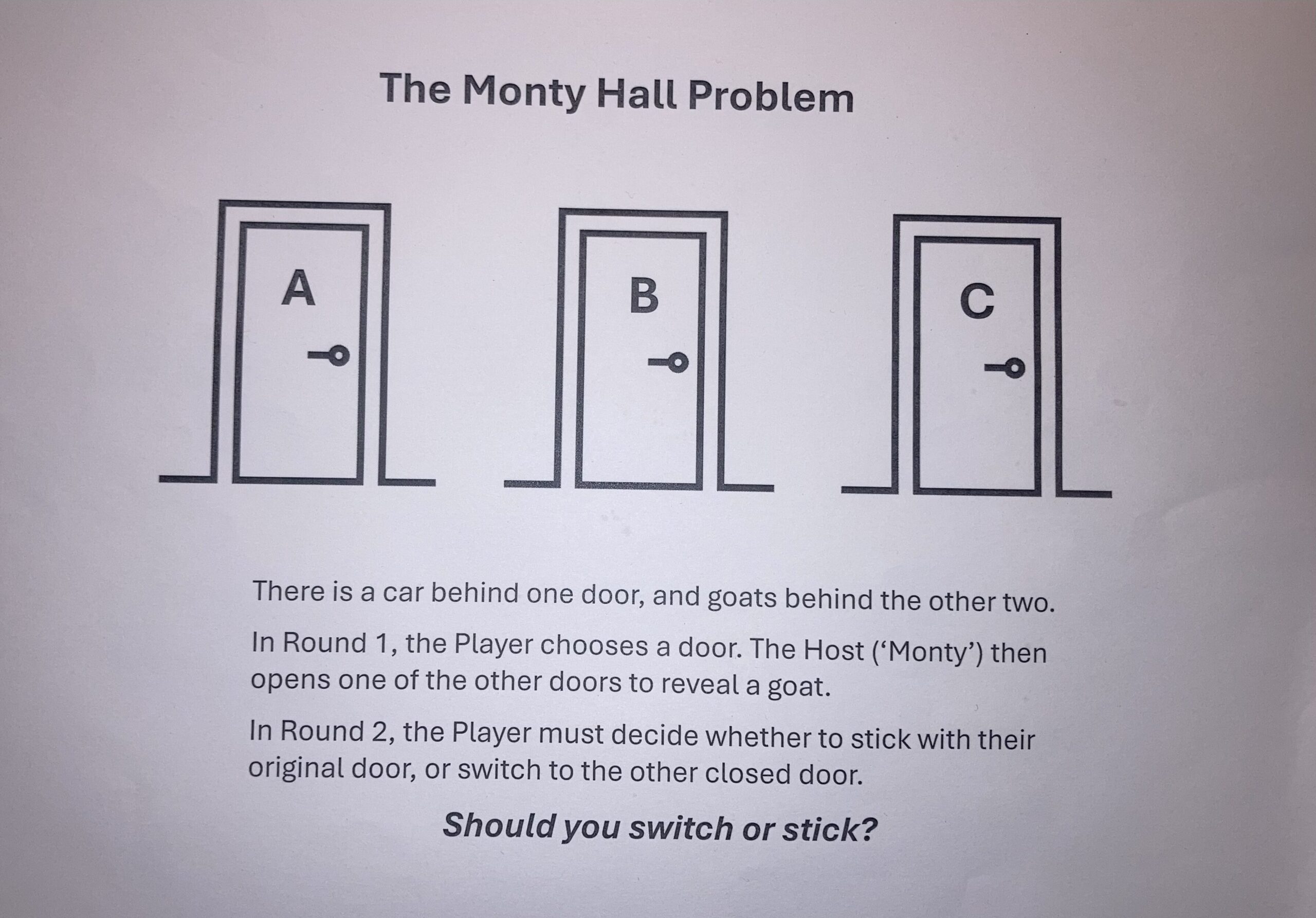

In her second handout, Kirsten presented us with the classic and completely counterintuitive Monty Hall problem. This problem, named after the host of the American TV Show ‘Let’s Make a Deal’, presents the player with three doors. One door has a car behind it, while the other two doors have goats behind. In the first stage, the player chooses a door, prompting the host to open a different door to reveal a goat. In light of this information, the player must then decide on whether to stick to their original door or switch to the other unknown door. Kirsten asked the audience what they thought they ought to do. Intuitively, some people answered that it surely doesn’t make a difference and that they backed their intuition. Others argued that while the original probability of getting a car was 1/3, it was now 1/2 as there are only two options, so it made no probabilistic difference whether they switched or not. However, many of the audience knew that you are meant to switch, without quite knowing why (a couple of people also gave convincing explanations as to why you switch).

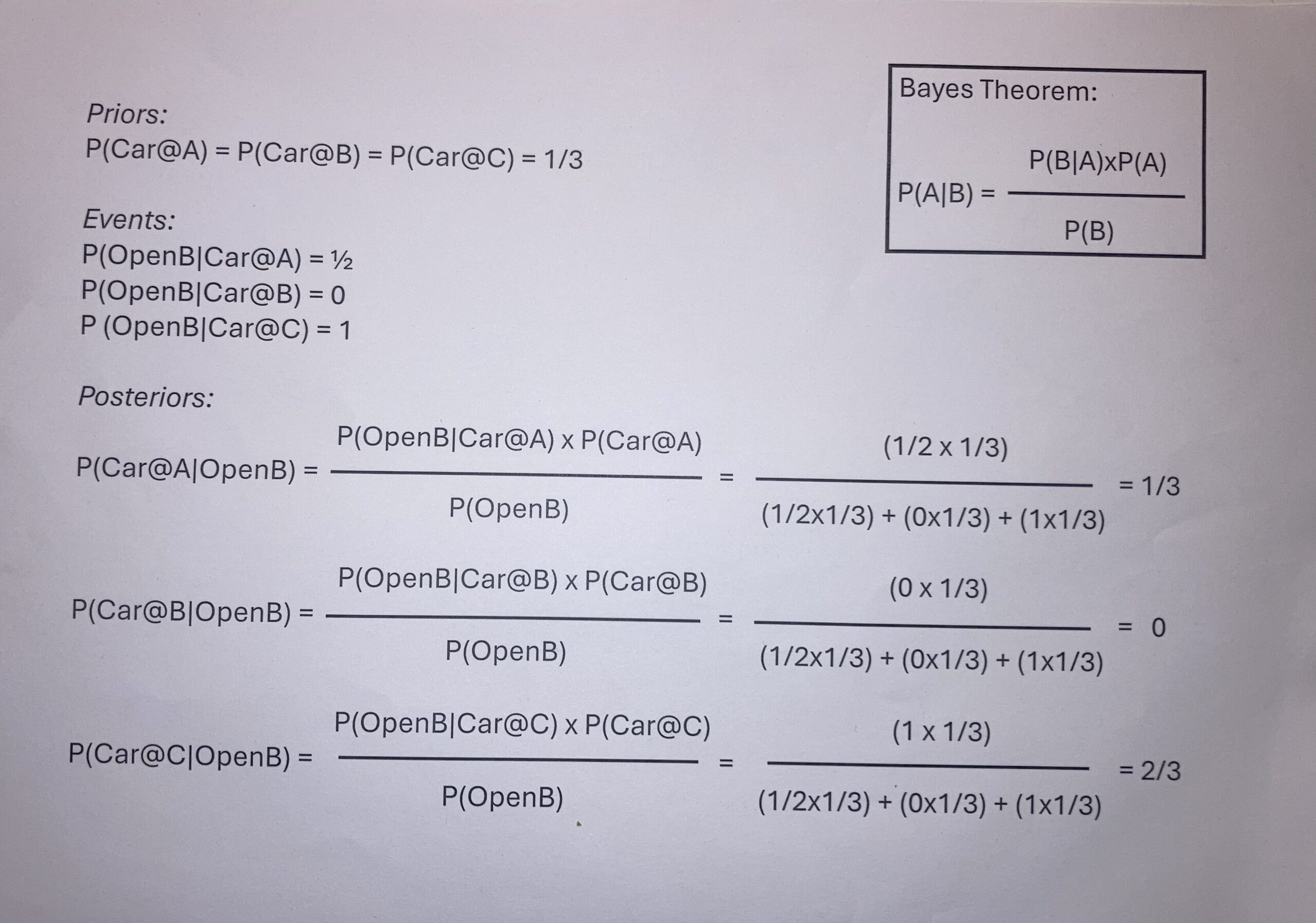

Kirsten then handed us a breakdown of the maths using Bayes’ Theorem. It helped almost no one, even with an explanation from Kirsten. The function that this handout really served was to prove that you should switch, even if most of us still did not understand why.

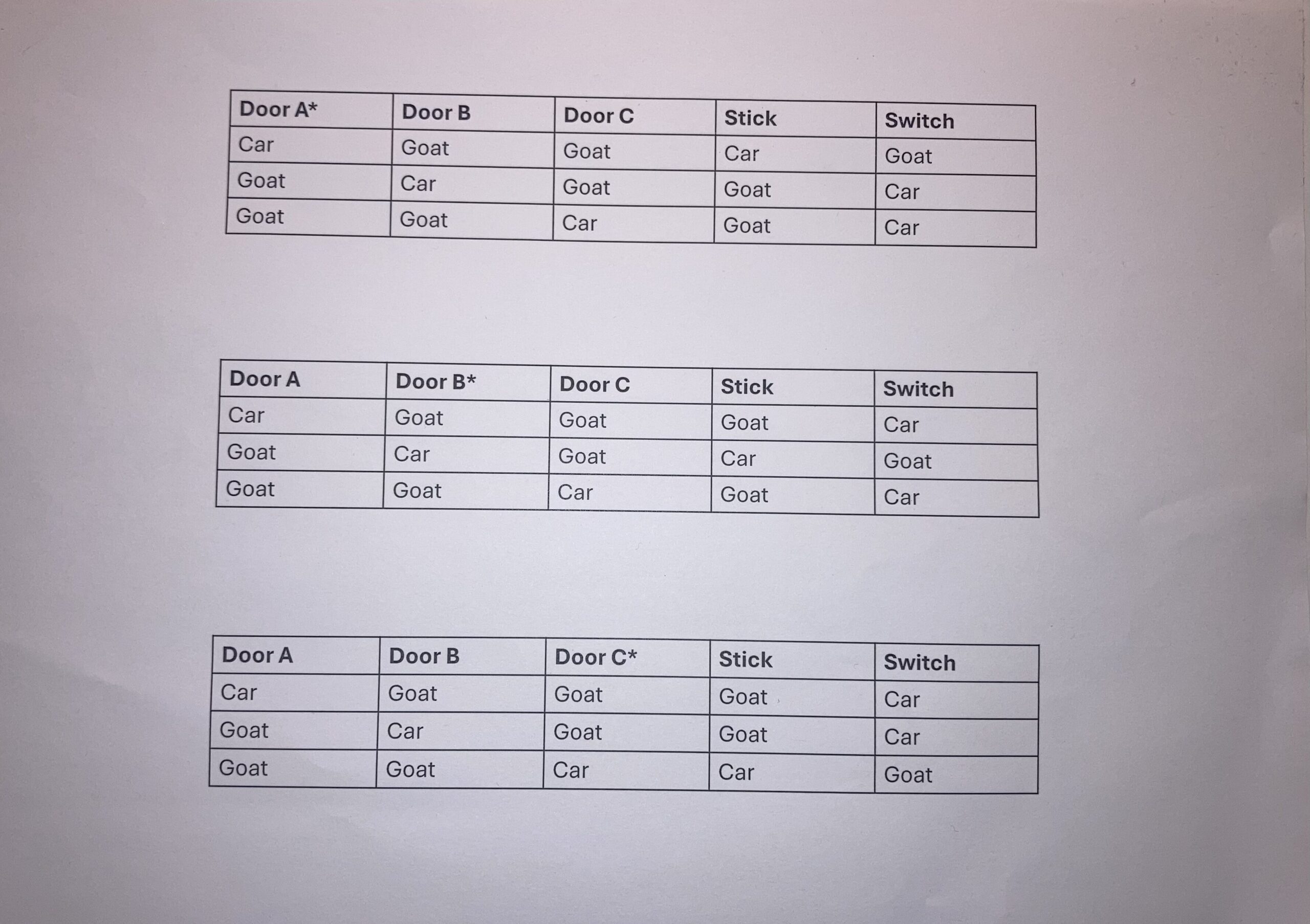

This is why Kirsten then handed us a table that broke down the probabilities instead. Here, the asterisk represents the initial choice of the player where all the possible iterations of the problem are then mapped out. It then becomes a lot clearer that while you are choosing between two options in the second part of the problem, the initial probability of 1/3 that you selected the door with the car carries over. Then, because the player knows that the chance of getting a car behind the door Monty reveals is 0, the probability of the car being behind the door that you switch to is 2/3.

The breakdown of the problem through a table made the answer much clearer to most people than verbal explanations and use of Bayes’ Theorem, allowing us to finally understand why you should switch. That being said, I still find the problem greatly counterintuitive, so bear with my explanation. The difficulty of fighting against your initial impression was however, much Kirsten’s point. She recounted a time that she put the problem to accountants she worked with. All of them denied that it could be true that you should switch and spent the day trying to prove mathematically, and incorrectly, why this was not the case. It took Kirsten a long presentation at the end of the day where she took the accountants manually through different iterations of the problem for them to agree that you should switch. This demonstrates Kirsten’s point that when facing some difficult or counterintuitive problems, different people require different forms of explanation before they can grasp the problem properly. This is different to knowledge of the correct answer (the state of the audience before Kirsten’s explanation of the Monty Hall Problem) and relates more to a feeling of deep understanding (the state of the audience after the simpler explanation). Kirsten wants to call this form of certainty, comprehensive certainty, which she argues isn’t captured by the other forms of certainty listed above. Kirsten also expressed the feeling that comprehensive certainty would fit into the section of certainties that compel assent as she sees similarities between the methods we might use to grasp something and mathematical proofs.

After this conclusion, the audience posed some particularly strong questions. One question expressed the worry that comprehensive certainty sounded similar to intuition. However, Kirsten argued that intuition has an immediacy to it and relates to problems we grasp without difficulty, while comprehensive certainty relates to less self-evident problems. A couple of other questions probed into the relation between comprehensive and psychological certainty. Kirsten argued that comprehensive certainty is different because it both relates to proper understanding and is therefore less emotional and easier to control. However, she did admit that it must be possible for comprehensive certainty to be false. This was picked up on by another question that argued that if comprehensive certainty doesn’t relate to facts, it ought to not compel assent. Kirsten maintained that she felt like comprehensive certainty should compel assent but conceded that she needed to flesh this idea out further.

That concludes this Phil on Tap summary, I hope you enjoyed!

Addition: I have been attending a new module that Kirsten runs called Philosophical Research, where lecturers come in to speak about their current research projects and the academic process they go through. In the first couple of weeks, Kirsten presented us with a project she is working on with Adrian Currie and Tom Roberts here in Exeter that looked to apply situated cognition to the optical experiments of Isaac Newton, which Newton believed compelled assent. They argue that a situated approach fits with Newton’s work through historical examples of how Newton placed great importance on experience in helping others understand his experiments. In light of this lecture and the Phil on Tap talk, I therefore asked Kirsten a couple of questions that she kindly answered.

Is Newton’s version of compelled assent in his optical experiments an example of your idea of comprehensive certainty?

If this is the case, is comprehensive certainty something that you arrive at through a situated cognition practice?

Kirsten’s response: Yes, Newton’s version of compelled assent (as I understand it) is an example ‘comprehensive certainty’. I think situated practice is certainly one way of arriving at comprehensive certainty, but probably not the only one. My thinking about this has largely developed through my trying to come to grips with Newton’s optical experiments. I’ve analysed his experiments in a bunch of different ways using a bunch of different philosophical tools – but in the end it comes down to more-or-less the same thing: as far as Newton is concerned, to know/grasp/have certainty, you have to experience the experimental sequence for yourself. This only seems to apply to cases where a single person can directly manipulate the target phenomenon, but it seems to exclude cases where you can’t have a direct experience. For example, when you’re studying things that are really far away (like stars), or complex phenomena that can’t be experienced all at once (like ecosystems), or the kinds of things that happen inside the Hadron Collider. I’d like to extend my analysis to say something about these cases. I’m not sure how yet, but it’s something I’m working on…

excellent read