Mimi Yates – 16/04/2022

In recent years the harmful effects of ‘lad culture’ has become of increasing concern amongst British univer- sities. Driven initially by NUS reports, Phipps & Young describe a “media storm” (2015: 306) with multiple headlines surfacing, discussing the out-of-control sexist behaviour infecting campuses. By examining the way lad culture is understood and explained, this essay will provide insights into the discourses that legitimise and perpetuate laddism in university contexts, specifically sport and heavy alcohol consumption. I will be drawing on three sets of data: the NUS 2010 ‘Hidden Marks’ Report on women students’ experiences of sexual harassment, Hales and Gannon’s 2021 empirical research on ‘Understanding Aggression in UK Male University Students’, and my own qualitative research to back up my analyses of explaining how laddism theorises into misogynistic attitudes that scaffold sexual harassment. In addition to understanding the negative impact of female students, It will also explain how lad culture sustains a hegemonic, unhealthy masculinity for men. The final part will discuss what is being done and what can be done, using case studies of UK based feminist movements such as ‘Everyone’s Invited’ and ‘Sit Down n Shut Up’. It will conclude that challenging laddism must aim to involve men in feminist discourse promoting a reformed positive masculinity, fostering authentic collaboration between men, women and institutions to promote solidarity.

What is Lad Culture?

“If the girl you’ve taken for a drink…won’t spread for your head, think about this mathematical statistic: 85% of rape cases go unreported. That seems to be fairly good odds. Uni Lad does not condone rape without saying ‘surprise’” – Uni Lad, cited in The Guardian (2012).

Perhaps a problematic term implying a generalisation which may not necessarily be wholly true and which may suggest ideas of determinism that should not be endorsed, ‘laddism’ has historically been a useful term in identifying the focus of research in this area, and it will be in context that I shall use it. Discourses of laddism first emerged in the UK in the 1950s with the distribution of ‘lad mags’ such as Playboy, before resurfacing prominently in the 1990s when worries of boys’ under-achieving educationally saw a focus on the image of “jack-the-lad” behaviours (Phipps & Young 2015: 2). Associated heavily with the Brit-Pop movement of this time, media from magazines like Loaded and sitcoms Men Behaving Badly presented images of hedonistic, hegemonic masculine values of male homosociality (ibid.,). Dempster (2007) specifically terms laddism as a“template” of hegemonic masculinity, noting on Connell’s conceptualisation of this term which argues that masculinities are multiple, hierarchical and constructed in antithesis to femininity (1995: 77). Following on, he argues that the majority of men are ‘complicit’ with this; perhaps reflecting the ideals within their gender performances, a concept central to the work of Judith Butler. Butler argues that although individual bodies become stylised by their gender performances, there are“collective dimensions to these actions” since performance’s aim is to keep gender within the binary frame (Butler 1988: 521). Thus, we can see how hegemonic masculinities can act within our society, and more spe- cifically, within our universities.

Seen by some as a bit of fun, as we see in the opening quotation to this section, lad culture can be heavily criticised by objectifying women and in this case normalising rape culture and glamorising sexual assault. Thus, Phipps and Young’s definition of lad culture as “a pack mentality in activities such as sport and heavy alcohol consumption, and ‘banter’ which is often sexist, misogynist and homophobic; which is also thought to be sexualised and involve the objectification of women, and at its extremes rape supportive attitudes and sexual harassment and violence” is what I shall be using throughout this paper (2013: 7). Inciting activities such as ‘Rate Your Shag’ pages on Facebook, sports team initiations titled ‘pimps and hoes’, wet t-shirt competitions and predatory sexual pursuits of first year girls called ‘sharking’ (termed at my own university), laddism can be inextricably linked to the sexual objectification de- scribed. In fact, Horvath and Hegarty found in their empirical research that members of the public were not able to differentiate between the language used in ‘lad mags’ and that of convicted sex offenders (2012). Appearing majorly (but not solely) amongst privileged middle-class men, research is able to provide a more in depth examination of this epidemic founded on the trinity of “drinking, football and fucking” (Phipps & Young 2015: 461 cited in Dempster 2009: 482).

Overview of data

I will be referring to three empirical sources:

1. NUS 2010, “Hidden Marks: A Study of Women Students’ Experiences of Harassment, Stalking, Violence and Sexual Assault

In 2010, a report was commissioned by the National Union of Students for researchers at the Gender Studies department at the University of Sussex to undertake research on campus culture and the experiences of women students’. 2058 students undertook a national online survey on their experiences of harassment, financial control, control over their course and institution choices, stalking, violence and sexual assault. The result of this research resulted in most UK literature surrounding lad culture, culminating in other NUS research papers such as ‘That’s What She Said’ (Phipps & Young 2015) .

2. Hales & Gannon 2021, “Understanding Sexual Aggres- sion in UK Male University Students: An Empirical As- sessment of Prevalence and Psychological Risk Fac- tors”

This recent report published in October 2021 is the first piece of research looking at sexual violence by heterosexual men rather than the effects on women victims. Men in the survey admitted to sexual assaults, rape and other coercive behaviour in the last two years, researchers from the University of Kent found. The research contained two surveys, one from 295 students from 100 UK universities and the other of 295 students at a specific university in south-east England. Participants were asked detailed questions on sexual scenarios as well as their views on women and relationships.

3. My own qualitative research

After defining terms, I launched a poll on the social media site ‘Instagram’ asking my peers the following questions: 1. Have you ever felt the effects of ‘lad culture’? If so, how? 2. Do you think lad culture has a negative ef- fect on women? 3. Do you think lad culture has a negative effect on men? 4. Do you feel pressured in assuming ‘lad culture’ mentality at university?. The first question were responded to in forms of personal testimonies, of which I received 9, and the subsequent questions were a ‘yes’/’no’ response. I had 218 participants for questions 2 and 3, of which 116 identified as male and 102 as female, and 89 participants for question 4 of whom all identified as male. I made sure that all of the participants in my study had previously studied or are currently studying at Exeter University in the UK. It is worth mentioning that the majority of my audience on social media will be white, middle-class and cisgender.

What contributes to lad culture on campus?

Fear of the Feminine

The aforementioned re-emergence of the ‘new lad’ mentality of the 1990s has been perceived as the time of the ‘crisis of masculinity’, linked to a cultural backlash of the gynocentric feminist ‘new man’ of the 70s and 80s, as well as men still having to be at the forefront of social concerns about jobs, family stability, failure in school and crime (Beynon 2002: 76). The word ‘crisis’ was used to evoke senses of masculinity under attack by high-achieving and assertive women, as a means of reclaiming androcentric territory in the ‘battle of the sexes’ (NUS 2013: Phipps 2013). This shift in gender norms left some men with a sense of insecurity and lack of position in society. Since men practising a hegemonic form of masculinity are more likely to place themselves at the centre of social discourse, we can conclude that the gynocentric nature of feminism presented a radical departure of this norm, leading to the conclusion form men that feminism stands directly in opposition to them (Crowe 2011).

It has also been argued that sexualised narratives in lad culture may partially emanate from an unease with women’s ‘self-actualisation’ (Phipps & Young 2015: 469). In my qualitative research, I asked my peers whether they had felt the effects of lad culture. One of the testimonials submitted by a female stated, “when boys go out and have lots of sex they are considered a stud but if girls do the same they are a slag”. The double standard expressed by this participant is less to do with sex but more so with sexism. Such gendered behaviours of objectification could again, present a backlash against new feminist constructions of sexual pleasure as opposed to make constructions of sexual possession. This analysis of laddism as a reassertion of traditional gender roles can be justified with statistics from research into sexual harassment, serving as tools to ‘put women back in their place’. Thus, the mentality within laddism we see today could be a continuation of these trends. For example, Hales & Gannon found that perpetrators were significantly more likely to be sexual assaulters if their psychological survey showed measures of hostility towards women (46%), rape myth acceptances (39%) and having sexual fantasies of hurting women without consent (56%) (2021:12). They concluded that sexually aggressive male university students are likely to be motivated to commit these offences by their high scores on these factors.

Sport

Similarly, the “you kick like a girl” style discourse em- bedded into male sporting cultures at university, translates male’s physical abilities into the subordination of women, as well as ‘less-laddy’ men. This language within sport emphasises the misogynistic, and homophobic, attitudes towards poor performance and the use of it to intimidate other teams. (Hearn 2004: cited in Dempster 2008). Schacht’s interesting paper on specifically gender in rugby (1996) notes on UK rugby players’ mentalities in purposely distancing themselves from the feminine, and referencing players with poor performances as “pussies” and “faggots” (Schacht 1996: 558). Dempster further notes that this is achieved through media, in that sportsmen’s achievements are celebrated highly and widely, whereas female sporting figures are virtually ignored. These figures live up to the ‘template’ of hegemonic masculinity and empower men to embody this authority this form of masculinity promotes. In addition, Salisbury and Jackson (1995: 205) mention how in British schools, sport is considered a ‘masculinising process’, meaning that strength and achievement are rewarded as a means to push boys into becoming ‘real men’ and drives a ‘survival of the fittest’ mentality (Schacht 1996). Thus, a man’s sporting ability is a “signifier of successful masculinity” (Dempster 2008: 483). Thirdly, aside from the actual playing of sport, Dempster mentions the “whole package” of other related activities that reinforce a hegemonic masculine ideal, such as “locker-room” banter, and initiation rituals (ibid.,). For example, one of the testimonials in my research of Exeter University students wrote that within the rugby team there was a “table of rankings made to rate all of the girls in the lacrosse team. Each column had a comment about how many shots it would take to them to get with her and number rankings for our ass and tits” (female student). A video caught the media’s attention in 2014, when a disturbing chant that surfaced from the University of Nottingham Athletics Union sang “now she’s dead, but not forgotten, dig her up and fuck her rotten” (The Guardian 2014). Such activities reiterate not only masculine superiority but also female objectification and rape cultures; all contributors to lad culture.

Alcohol

Included in Dempster’s (2007) “whole package” of university sporting activities is a heavy drinking culture. This is something not exclusive to sporting activities, but is a general student mentality in UK universities as a whole, since contact hours are minimal for the large majority of courses – leaving students with more free time and not as many responsibilities. Competitive drinking perpetuates an ‘in-grouping out-grouping’ style of inclusion and exclusion, alluding to performances like that in sport. In this way, pressure to drink from other males positions heavy drinking as an appropriate means of establishing masculinity (ibid.,). Alcohol-related male deaths in student societies prove within themselves the harm that this form of laddism causes, such as the case of Ed Farmer at Newcastle University (BBC News 2018). Interestingly, when asking my male peers at Exeter University in my research whether they felt pressure in assuming lad culture mentalities (such as heavy drinking cultures), 60% answered ‘no’ and 40% answered ‘yes’. However, my analysis of this purports that perhaps the overwhelming majority of those who answered ‘no’ were heavily involved in a ‘lad-like’ friend group; and so, are the ones pressuring rather than being pressured – or maybe are pressured unconsciously. In addition to being harmful to men, these drinking cultures also reinforce hostility against women as ‘lightweights’ are considered to be associated with being feminine. Dempster notes in his research a quote from participant Interviewee H: “females who drink a lot…that’s a turn off” (Dempster 2009: 642). It is also worth mentioning that this phenomena is not strictly bound to men. Women who take part in drinking cultures have been coined as ‘ladettes’, yet this is often used to degrade females’ gender performances as simply an “inferior masculinity” (Day, Gough & McFad- den 2004: 171). Therefore, heavy drinking cultures amongst men in higher education affirms gendered misogynistic discourses and its relationship with laddism.

Implications: Scaffolding Sexual Harassment

As demonstrated by the Hales & Gannon psychological evaluation in relation to sexual aggressors, it is evident that these misogynistic discourses within laddism contribute to sexual harassment. With my qualitative research, it was clear to see that my peer group overwhelming agreed on the negative impacts of lad culture for women, with 95% of men and women answering ‘yes’ to my poll. ‘Everyone’s Invited’, a movement started in June 2020 that exposes rape culture in the form of anonymous testimonies from students in UK schools and universities, puts more numbers to this. 84 institutions have been named, included University of Oxford (57 times), Edinburgh and Leeds (both 53 times), Uni- versity College London (48) and Exeter University with the most testimonies (65) (Everyone’s Invited 2021). It is vital to mention here that these numbers only indicate how many women were willing to come forward and write a testimony and is in no way indicative of the complete picture of sexual harassments occurring at UK universities, since NUS reported in their research that less than 20% of sexual assaults and violence go unreported (NUS 2010: 21).

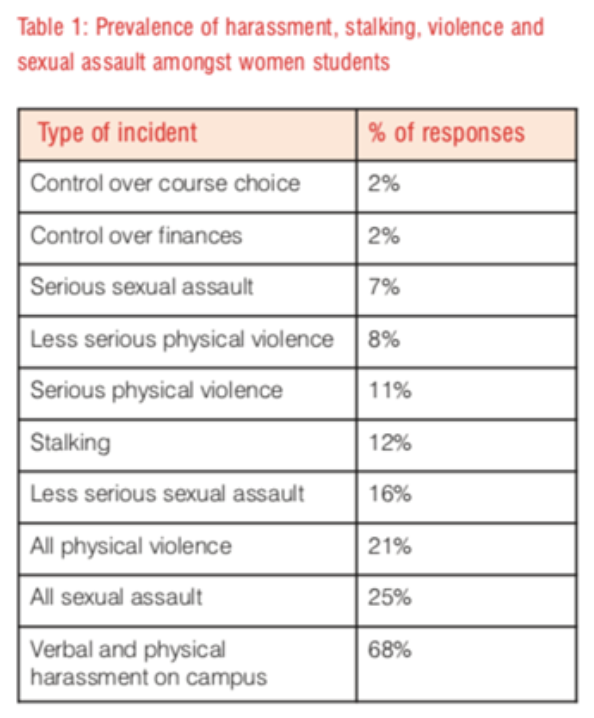

Key findings of the same NUS report state that 60% of women students have heard rape jokes on campus, while 68% of women students had been a victim of one or more kinds of sexual harassment on campus, and 25% experiencing a form of sexual assault (see table 1) (NUS 2010: 3).

In relating these horrifying statistic to laddism, Soma Sara, founder of ‘Everyone’s Invited’ spoke that “sexist beliefs, misogyny and toxic masculinity leads to predatory behaviour…[this] sexism is a part of a continuum of violence and when any individuals is dehumanised they become vulnerable to violence” (Sara in The Guardian 2021). Research from my second source similarly indicates, this time from the examination of male perpetrators, that out of the 554 male students that were surveyed, 63 reported that they had committed 251 sexual assaults, rapes and other coercive incidents in the last 2 years, with 37 reporting perpetrating unwanted sexual contact, 32 sexual coercion and 30 rape or attempted rape (Hales & Gannon 2021). They noted that, as mentioned, the strong association between rape supportive myths and misogynistic views including believing women who get drunk are to blame if they get raped, or having sadistic fantasies about torturing women, and committing acts of sexual aggression and violence. However, such views were not held by male students who did not report sexual aggression and violence (ibid., cited in The Guardian 2021). They conclude that the study shows the need for UK institutions to “step up their focus” on perpetrators whilst also providing appropriate support and action for victims following incidents (ibid.,). The fact that this research was entirely self-reported, en- tails an aspect must be considered. These are solely the men that are aware of what they have done, and in analysing this research we must take into account the proportion of men not just being surveyed, but in general, who are not aware that their actions count as sexual harassment, assault or violence; meaning the numbers pose a different, and perhaps a more shocking, reality.

Implications: a ‘toxic’ masculinity?

This theme of lad culture perpetuating a ‘toxic’ masculinity has been mentioned throughout this essay in the discussion of the contributors to laddism, but it must be given the time it deserves. In addition to Question 3 of my qualitative research asking whether my peers believed lad culture had negative impacts on women, I also asked in Question 4 whether they believed lad culture had negative impacts on men. I received the same result, with 95% answering ‘yes’ and 5% answering ‘no’. bell hooks notes on how damaging the “dominator model” is in contributing to “alpha maleness” mentalities in her book ‘Feminist Manhood’ (2004). Within this, other men who are not as dominating are ‘out-grouped’ by this collective identity if they do not conform, thus creating a sub-culture that makes these excluded men question their own masculine identities since the hyper-masculine ‘alphas’ promote themselves as the ‘real’ men. This constant power struggle has been noted on by American actor and activist Justin Baldoni in his book ‘Man Enough: Undefining my Masculinity’ and TED Talk entitled “It is exhausting trying to be man enough all the time” (Baldoni 2017). The current suicide rates for men should be looked at to fully realise the reality in Baldoni’s words.

It is important to mention that this ‘toxic’ masculinity promoted by laddism differs when we look at the intersection of race and gender. Historical damaging representations of black phallocentric masculinity have contributed as a further challenge, where white supremacist culture constructed the idea of the black masculine as dangerously sexual (bell hooks 1992). bell hooks notes on the highly damaging effects this has on the identity of some black men, whereby they have “absorbed” this mentality, for example through hip-hops pop-culture ‘crotch-grabbing’ pose, considered as a status symbol of male power for black male rappers (Lemons 1997: 37). Majors suggests that a reluctance to give up a focus on phallocentricism is thus a response to “black men being so conditioned to be guarded against oppression from white supremacist society” and so “this behaviour represents a safeguard against further abuse” (Majors 1992: 7). Consequently, some black women have been accused of “black male bashing” and reinforcing racist ideas of black masculinity, which is detrimental to the joint struggle of racist oppression, for both men and women (Lemons 1997: 42). This ties in to racism within laddism itself, for example during the Euro 2020 Football Final where Bukayo Saka and Marcus Rashford received a large amount of racism circling the internet after missing a penalty, stating their race as the reason for their sub-par performance (BBC News 2021). Therefore, the suffering within these male gender roles should not be glossed over, and is evidence that the ‘dominator model’, or as I have framed it throughout this essay, hegemonic masculinity within laddism, must be taken seriously.

What is being done, and what can be done?

In analysing the NUS ‘Hidden Marks’ report, the findings show that there were very low levels of institutional reporting (4%) (NUS 2010). It saw that only 65% of Student Union’s had a policy on sexual harassment, with a severe lack of promotion of the policy even if it was present. More recent headlines even show UK institutions being accused of silencing and covering up complaints to save reputations (see The Insider 2021). However, it must be noted that this report was published in over 10 years ago, and recent initiatives show that things are changing. Alongside ‘Everyone’s Invited’, Exeter University’s movement ‘Sit Down n Shut Up’ aims to expose and educate on lad culture in light of new sexual harassment statistics published by UN women that found 97% of women in the UK have been sexually harassed (UN Women UK: 2021). These initiatives aim to attack the culture rather than the individual, underlining female agency and encouraging feminist university societies to dismantle lad culture. In this, it should be recognised that in confining action to student groups there is a risk in rendering women as wholly accountable and hyper-responsible. Blaming all men for perpetuating lad culture can also exclude them from the discourse; meaning we get nowhere in changing the foundations of this behaviour. David Llewellyn, founder of The Good Lad initiative that aims promote a positive masculinity, warns that this “shuts many young men out of a conversations they need to be a part of” (Uni Health 2018). At the same time, we must make sure to preserve the gynocentricity of the negative implications of lad culture, in still encouraging initiatives within a university environment which can provide resources for such growth and development, and sustain the value of resistance to laddism taken from personal narratives such as these.

For these reasons, we should encourage what Phipps and Young term a “plurality of resistances” (2015: 479). Thus, instead of wiping men from the narrative, and assuming the man within the lad is rooted in sexism, we must promote reformed concepts of masculinity; and men must be willing to listen. bell hooks writes in her seminal text ‘Feminism is for Everybody’ (2014) that we must define masculinity as one that praises strength as “one’s capacity to be responsible for self and others” rather than dominate over others (bell hooks 2004: 12). To combat harmful elements of lad culture, we need men who encompass values of empathy, connectedness and self-responsibility and of others, and knowing that these are inseparable (ibid.,). In having male role models that embody this, men can take responsibility for themselves in coming to this understanding, and women will be able to have a better insight in comprehending elements of lad culture that they may not understand. This positive feminist masculinity can also include black men, since we must work to ensure the “de-colonization of black minds”, in a collective effort to actively oppose male dominant models that harm them and women alike (bell hooks 1992: 113). In this way, she describes how black men are in need of a reformed positive masculinity that does not have its grounding in racist phallocentrism (ibid., 112). Ultimately, encouraging feminist masculinity in an attempt to combat the harmful implications of lad culture could offer everyone solutions.

Conclusion

This paper has covered what lad culture is, where it has come from, and the negative impacts of this behaviour for both women in scaffolding sexual harassment, as well as for men in contributing to a harmful concept of masculinity. It has drawn on three sets of data by NUS, Hales and Gannon and from my own qualitative work, as well as using the case studies ‘Everyone’s Invited’ and ‘Sit Down n Shut Up’ to position these findings within the context of current movements in UK higher education. Finally, this paper has presented what is being done by institutions to dismantle lad culture, as well as presenting what could be done further, taking Phipps and Youngs’ research conclusions of collective action together with bell hooks’ academic work on promoting reformed positive masculinity. Through this, students and institutions can collaborate in fighting the negative impacts of laddism in UK higher education.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Baldoni, J. (2017). ‘Why I’m Done Trying to be Man Enough’. Ted Talk . Available at < https://www.youtube.com/watch? v=Cetg4gu0oQQ> [Accessed 15th April 2021]

- Majors, R. (1992). Cool Pose: The Dilemma of Black Manhood in America. United Kingdom: Touchstone.

- Lemons, G.L (1997). To Be Black, Male and “Feminist” – Making Womanist Space for Black Men. International Journal of Sociology and So- cial Policy, vol.27, no. 1/2, pp.35-61. Available at <https://doi.org/10.1108/eb013291>

- hooks, bell. (1992). Reconstructing Black Mascu- linity. Black Looks: Race and Representation, pp.87-114. Boston: South End Press.

- hooks, bell. (2004). Feminist Manhood. The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity and Love, ch. 7, pp. 107- 124. New York: Atria Books.

- Crowe, J. (2011). Men and Feminism: Some Chal- lenges and a Partial Response. Social Alternatives, vol. 20, no.1, pp.49-53. Available at <https:// ssrn.com/abstract=1945512> [Accessed 18th April 2021]

- Dempster, S (2009) Having the balls, having it all? Sport and constructions of undergraduate

- laddishness. Gender and Education 21(5): 481– 500.

- Dempster, S (2011) I drink, therefore I’m man: Gender discourses, alcohol and the

- construction of British undergraduate masculinities. Gender and Education 23(5): 635–653.

- Phipps, A. and Young, I. (2015) ‘‘Lad culture’ in higher education: Agency in the sexualization debates’, Sexualities, 18(4), pp. 459–479.

- UN Women United Kingdom (2021). ‘Public Spaces Need to Be Safe and Inclusive for All.

- Now’ [online] (10th March 2021) Available at < https://www.unwomenuk.org/safe-spacesnow>

- The Guardian (2021). ‘Research reveals rapes and assaults admitted to by male UK stu-

dents’ [online] (29th October 2021) Available at <https://www.theguardian.com/society/2021/ oct/29/research-reveals-rapes-and-assaults-admitted-to-by-male-uk-students> - Phipps, A., and Young.I (2013) That’s what she said: women students’ experiences of ‘lad cul- ture’ in higher education. Project Report. National Union of Students, London.

- Phipps, A and Young, I. (2010) “Hidden Marks: A Study of Women Students’ Experiences of Harassment, Stalking, Violence and Sexual Assault). Project Report. National Union of Students, Lon- don.

- Schacht, S. (1996). Misogyny on and off the ‘pitch’: The gendered world of male rugby players. Gender and Society, 10: 550–65.

- Salisbury, J. and Jackson, D. (1996). Challenging macho values: Practical ways of working with adolescent boys, London: Routledge Falmer

- Hearn, J. (2004). From hegemonic masculinity to the hegemony of men. Feminist Theory, 5(1): 49– 72.

- The Guardian (2012). ‘Uni Lad website closure highlights the trouble with male banter’ [online] (12th February 2012). Available at <https:// www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2012/feb/12/ uni-lad-website-closure-banter>

- UniHealth UK (2018). ‘Lad Culture: What’s the Harm?’. [online] (15th June 2018). Available at <https://unihealth.uk.com/lad-culture/>

- Butler, J. (1988). Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory. Theatre Journal, 40(4), 519–531.

- Day, K., B. Gough, and M. McFadden. (2004). ‘Warning! Alcohol can seriously damage your feminine health’: A discourse analysis of recent British newspaper coverage of women and drink- ing. Feminist Media Studies 4: 165–85

- Beynon, J. (2002). Masculinities and Culture. Management in Education. Open University Press

- Hales, S. and Gannon, A. (2021) Understanding Sexual Aggression in UK Male University Students: An Empirical Assessment of Prevalence and Psychological Risk Factors. Sex- ual Abuse. [online]. Available at journals.sagepub.com/doi/ full/10.1177/10790632211051682<

- Connell, R. (1995). Masculinities. University of California Press: USA.

- BBC News (2018). ‘Ed Farmer Inquest: Student died after ‘initiation style’ event. [online] (22nd October 2018). Available at <https:// www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-tees-45941336>

- The Guardian (2014). ‘First-year students ‘encouraged to sing necrophiliac chant’ by union reps’. (8th October 2014). Available at <https:// www.theguardian.com/education/2014/oct/08/ freshers-students-sing-necrophiliac-sexist- violent-chant>

- The Guardian (2021). ‘Schools abuse site Every- one’s Invited seeks ideas for ‘positive change’. [online] (4th April 2021). Available at <https:// www.theguardian.com/society/2021/apr/04/ schools-abuse-site-everyones-invited-seeks- ideas-for-positive-change>

- The Insider (2020). ‘UK universities have paid more than $1.6 million in hush money in the past few years to silence sexual assault accusers, according to a bombshell report’. [online] (12th February 2020). Available at <https:// www.insider.com/uk-universities-pay-13-million -siilence-sexual-assault-survivors-ndas-2020-2>